¶ LL-37: Benefits, Dosage, & Side Effects

| Sequence | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES |

| Formula | C205H340N60O53 |

| Molar Mass | 4493.3 g/mol |

| Category | Antimicrobial Peptide (AMP) |

| Half-life | Minutes (systemic); Hours (local) |

| Admin | Topical, SubQ (off-label) |

| FDA Status | Investigational / Not Approved |

| CAS | 154947-66-7 |

LL-37 is the only known human cathelicidin, a potent peptide that acts as a natural broad-spectrum antibiotic and immune system modulator. While clinical trials have shown promise for topical use in hard-to-heal wounds, systemic use is controversial due to potential risks of autoimmune activation and cancer promotion.

¶ At a Glance

What is it?

LL-37 (Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide) is a naturally occurring peptide produced by the human immune system. It serves as a "first line of defense," physically punching holes in bacterial membranes and signaling the immune system to repair tissue.

Primary Benefits

- Chronic Wound Healing: Significantly accelerates the closure of venous leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers in clinical trials.

- Biofilm Disruption: Potently breaks down bacterial biofilms (slime layers) that protect chronic infections from antibiotics.

Safety Profile

🔴 Caution (Systemic Use) / 🟡 Moderate (Topical Use)

- Topical: Generally well-tolerated in trials, though high doses can cause tissue irritation.

- Systemic: High risk of severe injection site reactions, mast cell activation (flushing/itching), and potential autoimmune flares. Theoretical cancer promotion risk in certain tissues.

¶ Protocol

| Variable | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Dosage (Topical) | 0.5 mg/mL – 1.6 mg/mL (applied as solution/cream) |

| Dosage (Systemic) | 100 mcg – 250 mcg (off-label/anecdotal) |

| Frequency | Topical: 2x/week Systemic: Daily |

| Cycle | Topical: 4 weeks Systemic: 4–6 weeks on, 4 weeks off |

| Route | Topical (primary); Subcutaneous Injection (off-label) |

Clinical Note: LL-37 follows a "bell-shaped" dose-response curve. In clinical trials, the lower dose (0.5 mg/mL) was more effective than the higher dose (3.2 mg/mL). More is not better; high concentrations are cytotoxic and impair healing.

¶ Benefits (The "Why")

¶ Chronic Wound Healing

The strongest clinical evidence for LL-37 is in the treatment of chronic, non-healing wounds.

- Venous Leg Ulcers: A randomized Phase II trial showed that topical application of LL-37 (0.5 mg/mL) significantly increased the healing rate of hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers compared to placebo [1]. Interestingly, higher doses (3.2 mg/mL) were less effective, suggesting a "goldilocks" zone for dosing.

- Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A 2023 randomized controlled trial found that LL-37 cream improved the healing rate and granulation tissue formation in diabetic foot ulcers [2].

¶ Biofilm Disruption

Bacteria often form "biofilms"—slime-like fortresses that protect them from antibiotics and the immune system. This is common in chronic infections like Lyme disease, chronic sinusitis, and infected implants.

- LL-37 has demonstrated a potent ability to penetrate and disrupt these biofilms at concentrations much lower than required to kill free-floating bacteria [3]. This property makes it a target of interest for treating persistent infections where standard antibiotics fail.

¶ Immune Modulation

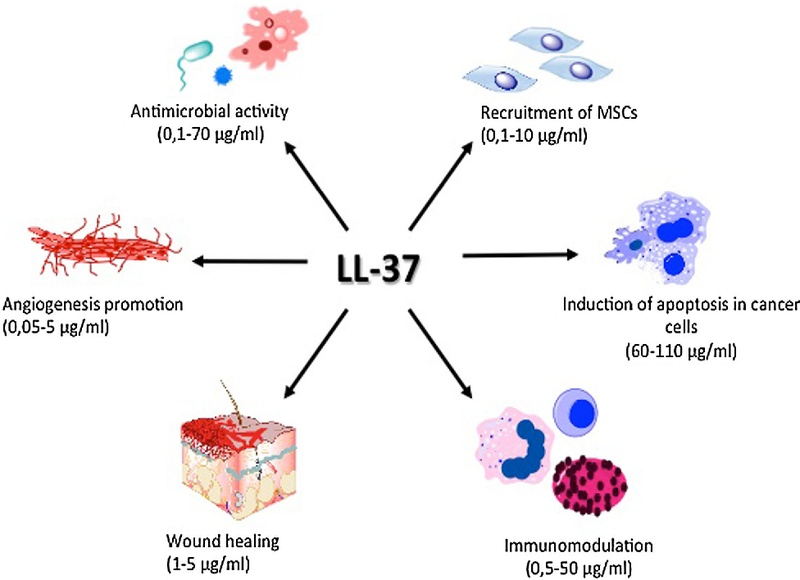

LL-37 does not just kill bacteria; it instructs the immune system.

- It recruits immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes, T-cells) to the site of infection (chemotaxis).

- It neutralizes bacterial toxins (like LPS), potentially reducing the risk of septic shock [4].

¶ Context & Biohacking Use

¶ The "Lyme & SIBO" Context

Despite the lack of FDA approval, LL-37 is widely discussed in biohacking and chronic illness communities (specifically Lyme disease and SIBO) for its biofilm-busting properties.

- Biofilm Theory: Many chronic conditions are believed by these communities to be driven by "persister" bacteria hiding in biofilms. LL-37's proven in vitro ability to disrupt biofilms is the primary driver of this off-label use.

- "Herx" vs. Toxicity: Users often report flu-like symptoms, flushing, and fatigue, interpreting them as a "Herxheimer" (die-off) reaction. However, these symptoms are often due to Mast Cell Activation (LL-37 triggers histamine release via the MrgX2 receptor) or systemic inflammation (IL-6 release), rather than bacterial die-off [5].

Reality Check: While LL-37 kills Borrelia (Lyme bacteria) in a petri dish [6], its rapid degradation in the blood (half-life in minutes) makes systemic efficacy challenging without advanced delivery systems.

¶ Mechanism of Action

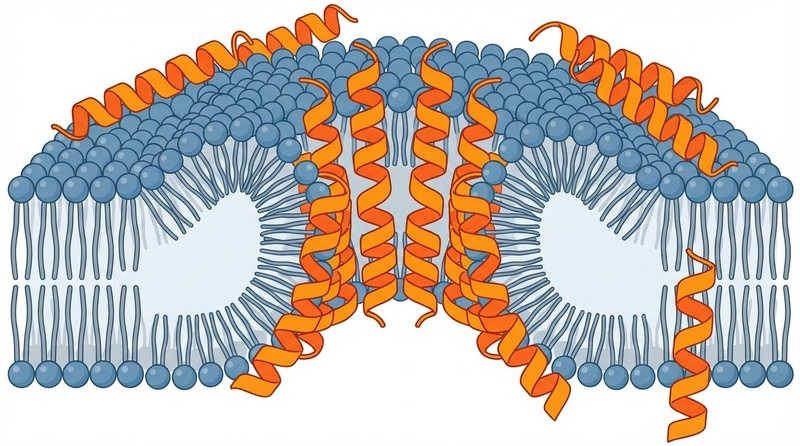

LL-37 operates through two primary mechanisms:

-

Membrane Disruption (The "Hole Punch" Effect):

LL-37 is positively charged. Bacterial membranes are negatively charged. This electrostatic attraction pulls LL-37 onto the bacterial surface. Once enough peptides gather, they insert themselves into the membrane and form toroidal pores [7]. This causes the bacterial cell to leak its contents and die. Because this mechanism is physical, it is much harder for bacteria to develop resistance compared to traditional antibiotics. -

Immune Signaling (The "Siren"):

LL-37 binds to specific receptors on human cells (such as FPR2 and P2X7) [8]. This triggers a cascade of effects:- Chemotaxis: Attracting immune cells to the war zone.

- Cytokine Release: Stimulating the production of IL-8 and IL-6 to ramp up inflammation.

- Angiogenesis: activating EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) to stimulate skin cell growth and new blood vessel formation, aiding wound repair [9].

¶ Evidence & Science

¶ Human Effect Matrix

| Outcome / Goal | Effect | Evidence Quality | Consistency | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous Leg Ulcer Healing | Positive | Moderate | Moderate | 2 RCTs; Topical 0.5–1.6 mg/mL, 2x/week for 4 weeks [1:1][10] |

| Diabetic Foot Ulcer Healing | Positive | Moderate | High | 1 RCT; Topical cream, significant improvement in granulation [2:1] |

| Chronic Otitis Media | Positive | Moderate | High | 1 RCT; Used synthetic derivative OP-145; 47% success vs 6% placebo [11] |

| Systemic Infection (Lyme) | Unclear | Very Low | Low | No RCTs; anecdotal only; based on in vitro data [6:1] |

¶ Key Studies

- Grönberg et al. (2014): A randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II trial in 34 patients with venous leg ulcers. Found that 0.5 mg/mL and 1.6 mg/mL topical LL-37 increased healing rates by 6-fold and 3-fold respectively, while 3.2 mg/mL showed no benefit [1:2].

- Kusumawardhani et al. (2023): A randomized double-blind trial on diabetic foot ulcers showing LL-37 cream significantly enhanced granulation tissue formation and healing speed compared to standard care [2:2].

¶ Safety & Side Effects

¶ Common Side Effects

- Injection Site Reactions: Severe redness, burning, swelling, and pain are very common with SubQ injection.

- Mast Cell Activation: Flushing, itching, heat sensation, and "pseudo-allergy" due to histamine release [5:1].

- Flu-like Symptoms: Malaise, fatigue (often mistaken for "Herxheimer" or die-off reactions).

¶ Serious Concerns

- Autoimmune Flares: Can trigger or worsen psoriasis, rosacea, SLE (Lupus), or other autoimmune conditions in susceptible individuals. High levels of LL-37 are a known driver of these diseases [12]. See Chronic Inflammation.

- Cancer Promotion: Theoretical risk of accelerating growth of existing tumors (breast, lung, ovary) due to angiogenic properties [13][14]. Conversely, it may suppress colon/gastric cancers.

¶ Contraindications

- Autoimmune Patients: Those with psoriasis, SLE, or rosacea should likely avoid LL-37.

- Cancer Patients: Due to angiogenic properties and unknown tumor interactions.

- Pregnant/Breastfeeding: Absolutely contraindicated due to unknown effects on fetal development.

¶ Legal & Regulatory Status

- FDA Status: Unapproved. LL-37 is not FDA-approved for any medical use. It is listed on the FDA's Category 2 Bulk Drug Substances list, meaning it raises "significant safety risks" (specifically regarding male reproduction and tumor promotion) and should not be compounded [15].

- WADA Status: Likely Prohibited. While not explicitly named, it falls under Category S2 (Peptide Hormones, Growth Factors) as a growth factor modulator affecting vascularization. Athletes should avoid it.

¶ References

Grönberg, A., et al. (2014). Treatment with LL-37 is safe and effective in enhancing healing of hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Wound Repair and Regeneration. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25041740/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Kusumawardhani, E., et al. (2023). Efficacy of LL-37 cream in enhancing healing of diabetic foot ulcer: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Archives of Dermatological Research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37480520/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Kang, J., et al. (2019). Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS ONE. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0216676 ↩︎

Nagaoka, I., et al. (2001). Cathelicidin family of antibacterial peptides CAP18 and CAP11 inhibit the expression of TNF-alpha by blocking the binding of LPS to CD14+ cells. The Journal of Immunology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11313405/ ↩︎

Niyonsaba, F., et al. (2001). Evaluation of the effects of peptide antibiotics human beta-defensins-1/-2 and LL-37 on histamine release and prostaglandin D2 production from mast cells. European Journal of Immunology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11298351/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Sapi, E., et al. (2011). Antimicrobial activity of bee venom and melittin against Borrelia burgdorferi. Antibiotics. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3223049/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Xhindoli, D., et al. (2016). The human cathelicidin LL-37: A pore-forming hexagonal II protein-lipid channel. Biophysical Journal. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26620092/ ↩︎

Scott, M. G., et al. (2002). The Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Is a Multifunctional Modulator of Innate Immune Responses. The Journal of Immunology. https://www.jimmunol.org/content/169/7/3883 ↩︎

Tokumaru, S., et al. (2005). Ectodomain shedding of EGFR ligands and TNFR1 dictates antimicrobial peptide LL-37-induced keratinocyte activation. The Journal of Immunology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16237107/ ↩︎

Grönberg, A., et al. (2011). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of the human cathelicidin LL-37 in patients with hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers. International Wound Journal. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00812.x ↩︎

Peek, F. A., et al. (2020). Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of the Safety and Efficacy of the Antimicrobial Peptide OP-145... Otology & Neurotology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32287316/ ↩︎

Kahlenberg, J. M., & Kaplan, M. J. (2013). Little Peptide, Big Effects: The Role of LL-37 in Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease. The Journal of Immunology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3836506/ ↩︎

Wu, W. K., et al. (2018). Roles and Mechanisms of Human Cathelicidin LL-37 in Cancer. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. https://karger.com/cpb/article/47/3/1060/75103/Roles-and-Mechanisms-of-Human-Cathelicidin-LL-37 ↩︎

Coffelt, S. B., et al. (2009). The pro-inflammatory peptide LL-37 promotes ovarian tumor progression through recruitment of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0900236106 ↩︎

FDA. (2023). Safety Risks Associated with Certain Bulk Drug Substances for Use in Compounding. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/certain-bulk-drug-substances-use-compounding-may-present-significant-safety-risks ↩︎