¶ Exercise

Everyone will tell you that exercise is healthy. But why? Let's find out.

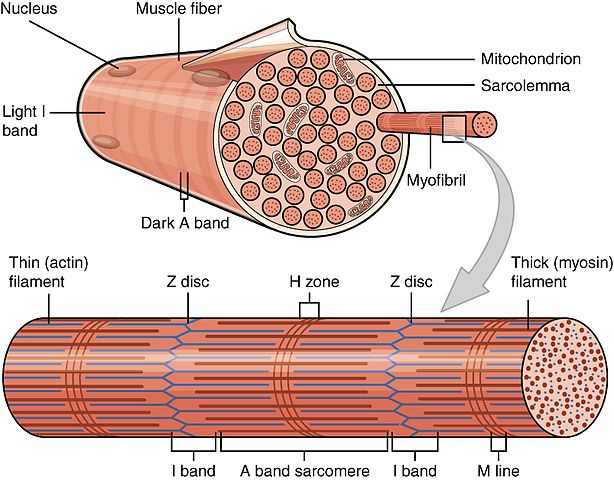

Scientific illustration showing the organization of muscle fibers, highlighting the different fiber types discussed in this article.

The first reason is that exercise stimulates the production and maintentance of muscle, which wastes as we age and is crucial for autonomy and quality of life.

The second is that skeletal muscle is an endocrine organ that secretes myokines regulating whole‑body metabolism. Aging preferentially erodes fast fibers and neuromuscular function; training counteracts these changes [1][2][3][4][5][6].

¶ Why exercise is healthy (mechanisms, table‑first)

A scientific illustration demonstrating how exercise triggers the release of myokines from skeletal muscle, illustrating the body's complex metabolic response to physical activity.

| Mechanism | Primary effect | Key outcomes | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preserve muscle mass and strength | Slows sarcopenia (age‑related muscle loss) | Maintains mobility, lowers disability and mortality risk | Observational cohorts; RCTs with hypertrophy/strength gains [4:1][5:1][6:1] |

| Endocrine signaling (myokines) | IL‑6, irisin, myostatin, IL‑15, BDNF, FGF21, BAIBA, METRNL, myonectin, SPARC, decorin, apelin | Improves insulin sensitivity, lipid oxidation, adipose browning, inflammation resolution, tissue repair | Mechanistic, human acute exercise, RCT/controlled studies [1:1][2:1][3:1][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] |

| Fiber‑type and neuromuscular preservation | Counteracts preferential atrophy/denervation of type II fibers | Maintains power, reduces falls risk, supports functional independence | Histology, longitudinal physiology, intervention trials [4:2][18][5:2] |

¶ 1) Muscle mass and autonomy

Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function with aging; it predicts disability, falls, and mortality [1:2][4:3]. Quantitatively, strength declines faster than mass (quality changes), e.g., longitudinal cohorts report marked losses in strength and muscle quality over time [4:4].

Resistance training in older and very old adults produces large, clinically meaningful gains in strength and fiber cross‑sectional area (CSA), demonstrating reversibility even in frailty [5:3][6:2].

Minimal numbers (illustrative):

- Health ABC: significant declines in strength and muscle quality over follow‑up despite modest mass loss [4:5].

- RCT (very old, mean ~87 y): ~2–3× increases in lower‑extremity strength after 8–10 weeks of high‑intensity resistance training [6:3].

¶ 2) Muscles are glands: skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ

Skeletal muscle secretes cytokines/peptides (myokines) into circulation during and after contraction, acting in autocrine/paracrine/endocrine fashions to regulate glucose and lipid metabolism, browning of adipose tissue, inflammation resolution, tissue repair, and brain function [1:3][2:2][3:2][7:1].

¶ Major myokines (selected) and their principal actions

| Myokine (acronym expanded once) | Principal actions | Typical context | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin‑6 (IL‑6) | Increases glucose uptake and fatty‑acid oxidation in muscle; lipolysis; anti‑inflammatory signaling acutely during exercise | Acute exercise → transient rise | Mechanistic and human exercise studies [1:4][12:1] |

| Irisin (cleaved from FNDC5) | Induces browning of white adipose tissue; increases thermogenesis and energy expenditure | Endurance/resistance exercise | Nature discovery; human observational/intervention data [8:1][13:1] |

| Myostatin (GDF‑8) | Negative regulator of muscle growth; inhibition → hypertrophy | Basal regulation; reduced with training | Genetic/mechanistic; translational relevance [19] |

| Interleukin‑15 (IL‑15) | Supports muscle anabolism; associated with lower adiposity | Exercise‑responsive | Human/biological studies [7:2][16:1] |

| Brain‑derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Increases fat oxidation via AMPK; muscle–brain axis (neurotrophic) | Muscle contraction; endurance exercise | Mechanistic and human cell work [9:1][7:3] |

| Fibroblast growth factor‑21 (FGF21) | Improves insulin sensitivity; regulates glucose/lipid metabolism | Acute and chronic exercise; metabolic stress | Human/mouse exercise/physiology [14:1][20] |

| β‑Aminoisobutyric acid (BAIBA) | Promotes hepatic β‑oxidation; induces browning of white fat | Exercise‑induced metabolite | Human associations; mechanistic data [10:1] |

| Meteorin‑like (METRNL) | Enhances beige fat thermogenesis; immune–adipose interactions | Cold/exercise | Cell and animal work with translational relevance [11:1] |

| Myonectin (CTRP15) | Increases fatty‑acid uptake; activates mTOR; suppresses hepatic autophagy | Exercise/muscle contraction | Mechanistic and in vivo studies [15:1][16:2] |

| Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) | Metabolic effects; exercise‑linked antitumorigenic signaling in colon | Regular exercise | Human tissue and animal mechanistic data [17:1] |

| Decorin | Binds/inhibits myostatin; contributes to hypertrophy | Resistance exercise | Human/animal mechanistic studies [21] |

| Apelin | Improves muscle function/regeneration; favorable metabolic effects | Aerobic training; aging muscle | Human cohort/intervention data [17:2] |

Notes: Acute IL‑6 elevations during exercise differ from chronic low‑grade inflammation; context (timing/tissue) determines net effect [1:5][12:2]. Evidence spans mechanistic, human acute exercise, and controlled training studies; not all myokines have definitive clinical outcome trials yet [2:3][7:4][22][23].

¶ 3) The loss of Type II (fast-twitch) fibers with aging

Schematic illustrating the preferential loss of Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers compared to Type I (slow-twitch) fibers over the human lifespan. While Type I fibers remain relatively stable, Type II fibers undergo significant atrophy and loss starting in mid-life. Modeled after data from Lexell et al. [18:1]

Human skeletal muscle comprises two primary fiber types: Type I (slow-twitch), which are fatigue-resistant and used for endurance; and Type II (fast-twitch), which generate high force and power but fatigue quickly. Aging does not affect these fibers equally.

¶ Preferential atrophy and loss

The age-related loss of muscle is predominantly a loss of Type II fibers.

- Selective Atrophy: Type II fibers shrink significantly in size (cross-sectional area), reducing by 25–40% or more between age 20 and 80 [18:2][24]. Type I fibers, in contrast, generally maintain their size.

- Motor Unit Loss: The alpha motor neurons that innervate Type II fibers are prone to apoptosis (cell death). As these neurons die, the associated muscle fibers lose their connection to the nervous system [18:3].

¶ The mechanism of "Grouping"

When a Type II fiber becomes denervated, it signals for help. Often, a nearby Type I motor neuron will sprout a collateral nerve to re-innervate the "orphaned" fiber. This saves the fiber from dying, but it comes at a cost: the fiber is converted from Type II to Type I [5:4][24:1].

- Result: The muscle becomes slower and less powerful.

- Clumped Architecture: Instead of the healthy "checkerboard" pattern of mixed fiber types seen in youth, older muscle shows "grouping" of fiber types, indicating this history of denervation and reinnervation [18:4].

¶ Clinical consequences: Power vs. Strength

Because Type II fibers drive high-velocity movement, muscle power (the ability to exert force quickly) declines much faster than pure strength [24:2]. This has critical implications for independence:

- Fall Risk: Recovering from a trip requires a split-second explosive step (Type II activity).

- Mobility: Rising from a chair or climbing stairs requires power.

- Solution: Resistance training, particularly with an intent to move the weight quickly (power training), can hypertrophy remaining Type II fibers and improve the firing rates of motor units, partially reversing this decline [5:5][6:4].

¶ Practical implications (evidence‑anchored)

An infographic illustrating the systemic benefits of exercise-induced myokines across different body systems.

- Prioritize resistance training (2–3×/week): increases strength and type II fiber CSA in older adults, including the very old/frail [5:6][6:5].

- Include aerobic work: supports myokine profile (IL‑6, FGF21, irisin, apelin), mitochondrial function, and cardiometabolic health [1:6][2:4][7:5][14:2][17:3][20:1].

- Progress gradually; monitor effort and recovery; combine with adequate protein to support hypertrophy (outside scope here).

¶ References

Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle‑derived interleukin‑6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1379‑1406. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.90100.2007 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Severinsen MCK, Pedersen BK. Muscle–organ crosstalk: the emerging roles of myokines. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(4):594‑609. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32374815/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Laurens C, Bergouignan A, Moro C. Exercise‑Released Myokines in the Control of Energy Metabolism. Front Physiol. 2020;11:91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7031345/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Goodpaster BH, et al. Loss of strength, mass, and quality in older adults (Health ABC). J Gerontol A. 2006;61(10):1059‑1064. https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/61/10/1059/545851 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Frontera WR, Meredith CN, O’Reilly KP, Knuttgen HG, Evans WJ. Strength conditioning in older men: hypertrophy and function. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64(3):1038‑1044. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/jappl.1988.64.3.1038 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND, et al. Exercise training in very elderly people (RCT). N Engl J Med. 1994;330(25):1769‑1775. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199406233302501 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Green DJ, et al. The Potential Role of Contraction‑Induced Myokines in Metabolic Regulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:97. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2017.00097/full ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Boström P, et al. A PGC1‑α‑dependent myokine (irisin) that drives browning of white fat. Nature. 2012;481:463‑468. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature10777 ↩︎ ↩︎

Wrann CD, et al. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF via a PGC‑1α/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metab. 2013;18(5):649‑659. https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(13)00372-3 ↩︎ ↩︎

Roberts LD, et al. β‑Aminoisobutyric acid induces browning of white fat and hepatic β‑oxidation. Cell Metab. 2014;19(1):96‑108. https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(13)00478-0 ↩︎ ↩︎

Rao RR, et al. Meteorin‑like regulates beige fat thermogenesis. Cell. 2014;157(6):1279‑1291. https://www.cell.com/fulltext/S0092-8674(14)00578-3 ↩︎ ↩︎

Akerström T, et al. Exercise induces IL‑6 release from human skeletal muscle; role in lipid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E733‑E740. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpendo.00340.2004 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Huh JY, et al. Irisin stimulates muscle growth‑related genes and regulates adipocyte metabolism in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:1538‑1544. https://www.nature.com/articles/ijo201442 ↩︎ ↩︎

Izumiya Y, et al. FGF21 is an Akt‑regulated myokine. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(27):3805‑3810. https://febs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1016/j.febslet.2008.10.021 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Seldin MM, et al. Myonectin (CTRP15) links skeletal muscle to systemic lipid homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(15):11968‑11980. https://www.jbc.org/article/S0021-9258(20)50094-2/fulltext ↩︎ ↩︎

Seldin MM, et al. Skeletal muscle‑derived myonectin activates mTOR to suppress hepatic autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(50):36073‑36082. https://www.jbc.org/article/S0021-9258(20)50092-3/fulltext ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Aoi W, Naito Y, Takagi T, et al. SPARC and exercise‑linked suppression of colon tumorigenesis. Gut. 2013;62(6):882‑889. https://gut.bmj.com/content/62/6/882.long ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Lexell J, Taylor CC, Sjöström M. Ageing atrophy: number/size/proportion of fiber types in vastus lateralis (15–83 y). J Neurol Sci. 1988;84:275‑294. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0022510X88901245 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass by a new TGF‑β family member (myostatin). Nature. 1997;387:83‑90. https://www.nature.com/articles/387083a0 ↩︎

Kim KH, Lee MS, et al. Acute exercise induces FGF21 in mice and humans. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63517. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0063517 ↩︎ ↩︎

Kanzleiter T, Rath M, Görgens SW, et al. The myokine decorin is regulated by contraction and involved in hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450(2):1089‑1094. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006291X14011089 ↩︎

Hoffmann C, Weigert C. Skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ: myokines in exercise adaptations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7(11):a029793. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28389517/ ↩︎

Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(8):457‑465. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrendo.2012.49 ↩︎

Verdijk LB, et al. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance training is accompanied by a fiber type-specific increase in satellite cell content in elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(3):332-339. https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/64A/3/332/625396 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎