¶ Elecampane (Inula helenium): Benefits, Dosage, & Side Effects

| Type | Herbal Supplement |

| Active Cmpd | Alantolactone, Inulin |

| Source | Root / Rhizome |

| Dose Range | 1–2 g (dried root) |

| Half-life | Unknown |

| Main Benefit | Respiratory Health |

| Absorption | Variable |

⸻

Elecampane (Inula helenium) is a traditional herbal remedy primarily used to support respiratory health and soothe coughs. While clinical evidence for the herb in isolation is limited, it remains a staple in Western herbal medicine for bronchitis and digestive stagnation due to its rich content of soothing inulin and antimicrobial sesquiterpene lactones.

⸻

¶ At a glance

Aliases

- Also known as: Horseheal, Elf Dock, Scabwort, Yellow Starwort.

- Botanical name: Inula helenium L.

- Category: Botanical (Root), Respiratory Tonic, Bitter.

Key points

- Strongest benefit: Historically validated and clinically supported (in combination formulas) for relieving acute cough and soothing irritated airways.

- Secondary effects: Acts as a prebiotic digestive aid due to high inulin content and possesses antimicrobial properties in laboratory studies.

- Key limitation: Nearly all human clinical data comes from multi-herb formulas, making it difficult to isolate elecampane's specific contribution.

- Safety concern: Potential for allergic reactions in individuals sensitive to the Asteraceae (ragweed) family.

What people use it for

- Main goals: Relief from bronchitis/cough, expelling mucus (expectorant), and improving digestion.

- Evidence quality: Low (for isolated herb) to Moderate (for multi-herb preparations).

⸻

¶ What is Elecampane?

Elecampane is a large, yellow-flowering perennial plant native to Europe and Asia, now naturalized in parts of North America. It belongs to the Asteraceae family, the same botanical family as sunflowers and ragweed.

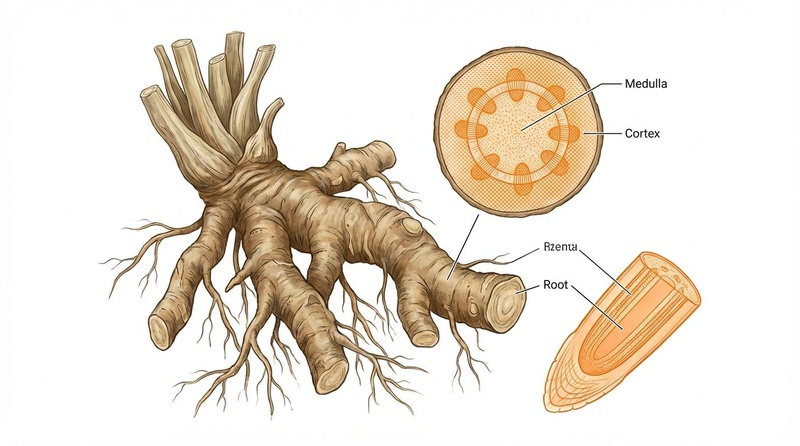

- Definition: A medicinal herb whose roots and rhizomes are harvested for their therapeutic compounds.

- Natural sources: The root of the Inula helenium plant.

- Traditional use: Used for centuries in Greek, Roman, and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as an expectorant for "damp" lung conditions, a digestive tonic, and even as a flavoring for absinthe and vermouth.

- Key pharmacological property: "Antimicrobial expectorant and prebiotic" — it helps clear mucus while fighting pathogens and feeding gut flora.

The root is distinctively aromatic with a bitter and pungent taste. It is one of the richest natural sources of inulin, a starchy polysaccharide that soothes mucous membranes and acts as a prebiotic fiber.

⸻

¶ What are Elecampane’s main benefits?

¶ Respiratory Health (Cough & Bronchitis)

Elecampane is most famous for its ability to treat respiratory ailments. Traditional herbalists classify it as a warming expectorant, meaning it helps loosen and expel mucus from the lungs.

- Outcome: Reduction in cough frequency and severity; improvement in "productive" coughs.

- Evidence: A 2021 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 106 children found that a cough syrup containing elecampane (alongside other herbs like Malva sylvestris) significantly reduced night-time and day-time cough compared to placebo[1].

- Mechanism: Sesquiterpene lactones (like alantolactone) have shown anti-inflammatory activity in human respiratory cells, potentially calming airway inflammation[2][3].

- Summary: Likely effective for soothing coughs and bronchitis, though modern evidence primarily comes from combination formulas.

¶ Digestive Health & Antimicrobial Activity

The root contains up to 44% inulin, a potent prebiotic that feeds beneficial gut bacteria (specifically Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli). Additionally, the bitter compounds stimulate digestion.

- Outcome: Improved gut flora balance; potential antimicrobial effects against pathogens.

- Evidence: In vitro (test tube) studies demonstrate that elecampane extracts have significant antibacterial and antifungal activity, particularly against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida species[4][5].

- Note: While promising, these antimicrobial effects have not yet been validated in human clinical trials for treating infections.

¶ Anti-Inflammatory & Antioxidant Effects

Preclinical research suggests elecampane has broad anti-inflammatory properties.

- Outcome: Reduction of inflammatory markers (like NF-κB and TNF-α).

- Evidence: Animal and cell studies show that alantolactone can inhibit inflammation in various tissues, suggesting potential utility in conditions characterized by chronic inflammation[6].

- Status: Very Low certainty for clinical application, as this is currently limited to preclinical research.

⸻

¶ Evidence summary table (human outcomes)

| Outcome / Goal | Effect | Consistency | Evidence quality | Trials | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough Relief (Pediatric) | ↓↓ (p) | Moderate | Moderate | 1 RCT | Tested as part of a multi-herb syrup ("KalobaTUSS")[1:1] |

| Digestive Health | ↔ / ? | Low | Very Low | 0 RCTs | Based on inulin content and traditional use; no direct trials |

| Antimicrobial | ? | Low | Very Low | 0 RCTs | Strong in vitro data; no human infection trials |

⸻

¶ How does Elecampane work?

Elecampane’s effects are driven by two main groups of bioactive compounds: sesquiterpene lactones and polysaccharides.

¶ 1. Sesquiterpene Lactones (Alantolactone & Isoalantolactone)

These volatile compounds give the root its bitter taste and antimicrobial properties.

- Anti-inflammatory: They inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, a master regulator of inflammation. This helps reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines in respiratory and digestive tissues[2:1][6:1].

- Antimicrobial: They disrupt the cell membranes of bacteria and fungi, preventing their growth. This supports the traditional use of elecampane for bacterial bronchitis and intestinal parasites[4:1].

¶ 2. Inulin (Polysaccharide)

Elecampane root is one of the highest natural sources of inulin.

- Demulcent: Inulin forms a soothing, mucilaginous coating over irritated mucous membranes in the throat and gut.

- Prebiotic: It passes undigested into the colon, where it is fermented by beneficial bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that nourish the gut lining and regulate immunity.

⸻

¶ Effects on different systems

¶ Respiratory System

This is the primary target for elecampane. The volatile oils (lactones) are believed to be partially excreted through the lungs, where they exert direct antiseptic and expectorant effects. It is particularly valued for "stuck" coughs where mucus is difficult to expectorate.

¶ Digestive System

As a "bitter tonic," elecampane stimulates the secretion of saliva and gastric juices, potentially aiding appetite and sluggish digestion. The high inulin content supports the microbiome, though in sensitive individuals, it can cause gas and bloating due to fermentation.

¶ Immune System

By reducing systemic inflammation and supporting the gut microbiome (where 70% of the immune system resides), elecampane may offer indirect immune support, though this is less directly studied than its local effects on the lungs.

⸻

¶ Dosage and how to take it

Since there is no standard pharmaceutical dose, recommendations are based on traditional monographs (e.g., Commission E, ESCOP) and modern herbal practice.

¶ Common Forms & Dosages

- Dried Root (Tea/Decoction): 1.5 – 3 grams of dried root per day.

- Preparation: Simmer 1 tsp of dried root in 1 cup of water for 10–15 minutes. Drink warm 2–3 times daily.

- Tincture (Liquid Extract): 1:5 ratio in 45% alcohol.

- Dosage: 2–5 mL, taken 3 times daily.

- Capsules: typically 300–500 mg of root powder, taken 1–2 times daily.

¶ Usage Tips

- Taste: The tea is quite bitter and aromatic. It is often sweetened with honey (which also helps a cough) or blended with better-tasting herbs like licorice or ginger.

- Duration: Generally used for acute conditions (1–2 weeks). Long-term safety for months or years has not been established.

⸻

¶ Safety and side effects

Elecampane is generally considered safe for short-term use in appropriate dosages, but it has specific contraindications.

¶ Common Side Effects

- Digestive upset: High doses can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or stomach spasms due to the irritating nature of the lactones.

- Inulin response: Bloating and gas can occur in those sensitive to FODMAPs or high-fiber foods.

¶ Allergies (Important)

- Asteraceae Sensitivity: Elecampane is in the same family as ragweed, marigolds, daisies, and chrysanthemums. Individuals with allergies to these plants may experience an allergic reaction (rash, difficulty breathing) to elecampane.

¶ Warnings & Contraindications

- Pregnancy & Breastfeeding: Avoid use. There is insufficient safety data, and historical texts suggest it may stimulate the uterus (emmenagogue effects).

- Diabetes: Because inulin can affect blood sugar metabolism, individuals on insulin or hypoglycemic drugs should monitor their levels closely, though the risk is generally low.

⸻

¶ Drug and supplement interactions

Information on specific drug interactions is limited, but theoretical interactions exist based on its pharmacology.

Potential Interactions

- Sedatives (CNS Depressants): Theoretically, elecampane might extend the effects of sleep medications or anesthetics, though this is not well-documented.

- Blood Pressure & Sugar Meds: Due to potential mild diuretic and metabolic effects, it could theoretically potentiate medications for hypertension or diabetes.

- Interaction Consistency: Low. Most interactions are speculative rather than observed in clinical settings.

⸻

¶ Practical questions (FAQ)

1. Is elecampane good for a dry or wet cough?

It is traditionally used for both, but it excels at "wet" coughs where mucus is stuck. Its expectorant action helps liquefy and move phlegm, while its demulcent (soothing) properties help calm the irritation of a dry, hacking cough.

2. Can I take elecampane every day for prevention?

It is not typically used as a daily preventive supplement like Vitamin D. It is best used acutely for 1–2 weeks when you have respiratory symptoms or digestive stagnation.

3. Does it taste bad?

Yes, for most people. It is bitter, camphor-like, and pungent. Tinctures or capsules are preferred by those who cannot tolerate the strong flavor of the tea.

4. Is it safe for children?

The "KalobaTUSS" trial suggests it can be safe in pediatric formulations under medical supervision. However, because home dosing is difficult and allergy risks exist, consult a pediatrician before giving raw herbal extracts to children.

⸻

¶ How we evaluated the evidence

- Emphasis on Human Data: We prioritized the limited human clinical trials available, specifically the randomized pediatric trial.

- Grading: We rated the evidence for respiratory benefits as "Moderate" in the context of combination formulas but "Low" for the isolated herb due to a lack of specific monotherapy trials.

- Transparency: We clearly distinguished between traditional knowledge (centuries of use) and modern clinical validation (which is still emerging).

⸻

¶ References

Cohen, H. A., et al. (2020). Efficacy and safety of the syrup "KalobaTUSS®" as a treatment for cough in children: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02490-2 ↩︎ ↩︎

Gierlikowska, B., et al. (2020). Inula helenium and Grindelia squarrosa as a source of compounds with anti-inflammatory activity in human neutrophils and cultured human respiratory epithelium. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2019.112311 ↩︎ ↩︎

Kenny, C. R., et al. (2022). From Monographs to Chromatograms: The Antimicrobial Potential of Inula helenium L. (Elecampane) Naturalised in Ireland. Plants (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11030423 ↩︎

Stojković, D., et al. (2015). Antibacterial activity of Inula helenium root essential oil: Synergistic potential, anti-virulence efficacy and mechanism of action. Industrial Crops and Products. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.01.037 ↩︎ ↩︎

Deriu, A., et al. (2008). Antimicrobial activity of Inula helenium L. essential oil against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and Candida spp. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.020 ↩︎

Chun, J., et al. (2012). Alantolactone inhibits the production of inflammatory mediators via down-regulation of NF-κB and MAPKs signaling in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. International Immunopharmacology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2012.08.006 ↩︎ ↩︎